Hi.

The top-end of the size of your adventure area doesn’t matter in the short-term; the start of the first adventure session. What matters is do you have the means to procedurally generate the wilds in between the points of interest?

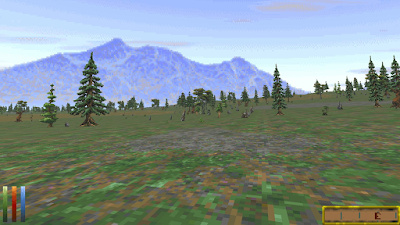

A map of known locations, even only one: the start point, is all that is necessary to begin filling in the map as it is explored. However, if you have two or more points, A). and B)., then it becomes more important to know specifics. If A). is known to be an unknowably ancient tower, partly ruined, of an unnamed stone, and the surrounding terrain is the hilltop upon which it is perched, surrounded by a dense and shady forest of thorny brambles, and only from the sparse windows of the tower where the PCs begin play can one see out beyond the brambles, then only those specific locations one can see need be defined to any degree.

Let’s say that B). is an outcropping of rock from which what appears to be a waterfall cascades shimmering in the distance, and although no pool can be seen, around which what appear to be reeds and sedges, perhaps even bracken/ferns are clustered. If everything between the tower and this site is seemingly open grassland, then only incidental ground clutter and encounters need be determined if the PCs travel to B).

Now, let’'s say that a table in the tower which has a vague map painted on its surface. The table is too large to carry, and so the PCs must, at best, attempt to copy the details on their mapping supplies. What is the scale? No indication. Which direction is North? Not indicated. Yes, using the tower and taking the time to follow the course of the sun will show where sunset is, if this occurs here, but what does it mean in relation to North or South if this is a foreign world/planet? Without the ability to determine direction, those details become relatively unimportant and only reinforces the point-to-point travel in the short and immediately foreseable long-term future for the PCs. This gives you a lot of freedom in determining everything that may become important later.

Other locales, say, C). is a plume of smoke rising beyond the horizon which is defined by a continuation of the twisted and gnarly, lifeless bramble forest. This creates a terrain-type which has its own ecosystem (assuming this isn’t a fairytale world of absolutes) which will have sub-sets based upon the presence of water, cliffs, rifts, and all manner of terrain features now obscured from view by both distance and the intervening brambles. Et cetera.

It can be open and unknown to its native population, excepting those locations to which travel has been made somewhat reliable through the dangerous work of initial scouts, and then, trailblazers, and eventually traders, settlers, merchants, and support service industry folk (craftsfolk, labourers, specialists, etc.) D). is marked on the map as, ‘Pigiron’, and is depicted as being on or near a river or stream. E). lies in the opposite direction from both the plume of smoke and Pigiron, and is merely a note and a symbol on the map: ‘Dangerous ground’.

Constraining all initial input, let alone expectations, and channeling travel towards specific areas helps you as GM to pace your preparation schedule, while still allowing complete freedom for the players to explore. Philosophical questions of Player Agency in the form of, ‘Meaningful Choice’, in light of a procedurally generated terrain exploration seem unhelpful to me: no one knows anything for themselves until they experience it, and no amount of outside information can be relied upon to deliver experiential truth: ‘There is a place called Paris, it is beautiful at night.’ OK, but until one sees Paris, etc. for oneself, Paris not only doesn’t exist, but its meaning to the individual cannot exist, That’s a lot like a procedurally generated exploration experience for imaginary people moving from point to point in an imaginary world.